A study led by scientists at Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU) has decoded the genomes of the deep-sea clam (Archivesica marissinica) and the chemoautotrophic bacteria (Candidatus Vesicomyosocius marissinica) that live in its gill epithelium cells. Through analysis of their genomic structures and profiling of their gene expression patterns, the research team revealed that symbiosis between the two partners enables the clams to thrive in extreme deep-sea environments.

The research findings have been published in the academic journal Molecular Biology and Evolution.

Due to the general lack of photosynthesis-derived organic matter, the deep-sea was once considered a vast “desert” with very little biomass. Yet, clams often form large populations in the high-temperature hydrothermal vents and freezing cold seeps in the deep oceans around the globe where sunlight cannot penetrate but toxic molecules, such as hydrogen sulfide, are available below the seabed. The clams are known to have a reduced gut and digestive system, and they rely on endosymbiotic bacteria to generate energy in a process called chemosynthesis. However, when this symbiotic relationship developed, and how the clams and chemoautotrophic bacteria interact, remain largely unclear.

Horizontal gene transfer between bacteria and clams discovered for the first time

A research team led by Professor Qiu Jianwen, Associate Head and Professor of the Department of Biology at HKBU, collected the clam specimens at 1,360 metres below sea level from a cold seep in the South China Sea. The genomes of the clam and its symbiotic bacteria were then sequenced to shed light on the genomic signatures of their successful symbiotic relationship.

The team found that the ancestor of the clam split with its shallow-water relatives 128 million years ago when dinosaurs roamed the earth. The study revealed that 28 genes have been transferred from the ancestral chemoautotrophic bacteria to the clam, the first discovery of horizontal gene transfer—a process that transmits genetic material between distantly-related organisms —from bacteria to a bivalve mollusc.

The following genomic features of the clam were discovered, and combined, they have enabled it to adapt to the extreme deep-sea environment:

(1) Adaptions for chemosynthesis

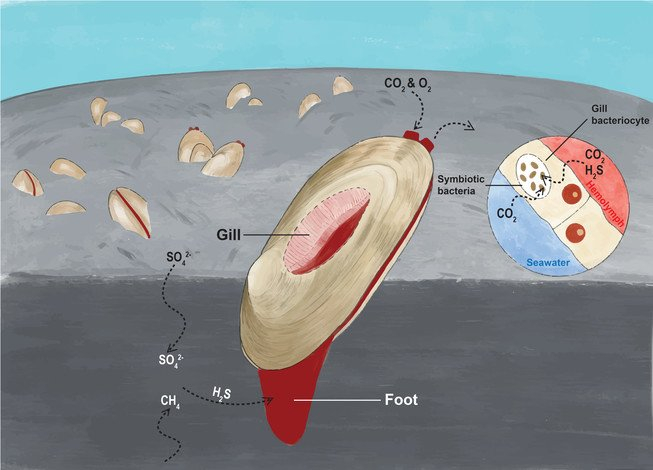

The clam relies on its symbiotic chemoautotrophic bacteria to produce the biological materials essential for its survival. In their symbiotic relationship, the clam absorbs hydrogen sulfide from the sediment, and oxygen and carbon dioxide from seawater, and it transfers them to the bacteria living in its gill epithelium cells to produce the energy and nutrients in a process called chemosynthesis. The process is illustrated in Figure 1.

The research team also discovered that the clam’s genome exhibits gene family expansion in cellular processes such as respiration and diffusion that likely facilitate chemoautotrophy, including gas delivery to support energy and carbon production, the transfer of small molecules and proteins within the symbiont, and the regulation of the endosymbiont population. It helps the host to obtain sufficient nutrients from the symbiotic bacteria.

(2) Shift from phytoplankton-based food

Cellulase is an enzyme that facilitates the decomposition of the cellulose found in phytoplankton, a major primary food source in the marine food chain. It was discovered that the clam’s cellulase genes have undergone significant contraction, which is likely an adaptation to the shift from phytoplankton-derived to bacteria-based food.

(3) Adaptation to sulfur metabolic pathways

The genome of the symbiont also holds the secrets of this mutually beneficial relationship. The team discovered that the clam has a reduced genome, as it is only about 40% of the size of its free-living relatives. Nevertheless, the symbiont genome encodes complete and flexible sulfur metabolic pathways, and it retains the ability to synthesise 20 common amino acids and other essential nutrients, highlighting the importance of the symbiont in generating energy and providing nutrients to support the symbiotic relationship.

(4) Improvement in oxygen-binding capacity

Unlike in vertebrates, haemoglobin, a metalloprotein found in the blood and tissues of many organisms, is not commonly used as an oxygen carrier in molluscs. However, the team discovered several kinds of highly expressed haemoglobin genes in the clam, suggesting an improvement in its oxygen-binding capacity, which can enhance the ability of the clam to survive in deep-sea low-oxygen habitats.

Professor Qiu said: “Most of the previous studies on deep-sea symbiosis have focused only on the bacteria. This first coupled clam–symbiont genome assembly will facilitate comparative studies that aim to elucidate the diversity and evolutionary mechanisms of symbiosis, which allows many invertebrates to thrive in ‘extreme’ deep-sea ecosystems.”

The research was jointly conducted by scientists from HKBU and the HKBU Institute for Research and Continuing Education, the Hong Kong Branch of the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Guangzhou), The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, City University of Hong Kong, the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, the Sanya Institute of Deep-Sea Science and Engineering, and the Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey.

Source: Communication and Public Relations Office, HKBU

由香港浸會大學(浸大)領導的一項研究,破解了俗稱「白瓜貝」的深海蜆(Archivesica marissinica),以及存活於其鰓中的化能自養細菌(Candidatus Vesicomyosocius marissinica)的基因組。通過分析他們的基因組及基因表達模式,研究團隊揭開了兩者的共生關係,以及如何讓白瓜貝在深海的極端環境中生存的分子機制。

有關研究結果已發表於國際學術期刊《分子生物與進化》。

由於缺乏光合作用衍生的有機物,深海一度被認為是生命荒漠,只有極少量生物棲息。然而,白瓜貝經常大量出現於全球深海的海底熱泉和冷泉區。在這些深海環境中,陽光無法穿透,而硫化氫等有毒物質則從海床釋放。白瓜貝的腸道和消化系統已經退化,依賴鰓表皮細胞內的共生細菌通過「化能合成」的方式獲取能量與營養物質。但這種共生關係從何時建立起來,以及白瓜貝與其共生細菌之間如何進行營養互補仍然不詳。

首次發現蜆與細菌間的「水平基因轉移」

由浸大生物系副系主任兼教授邱建文教授帶領的研究團隊,從南中國海一處1,360米深的冷泉區採集了白瓜貝樣本,然後對牠及其共生細菌的基因組進行測序,探究兩者成功建立共生關係背後的基因組特徵。

團隊發現早在1.28億年前的恐龍年代,白瓜貝的祖先已經從牠們的淺水近親分化出來。是次研究顯示白瓜貝基因組中含有28個基因是從化能自養細菌的祖先轉移而來。這是首次發現有基因通過「水平基因轉移」從細菌轉移至雙殼軟體動物。「水平基因轉移」是把遺傳物質在沒有遺傳關係的物種之間傳遞的過程。

研究還發現白瓜貝有着以下的特徵,有利牠們很好地適應極端的深海環境:

(一)化能合成作用

白瓜貝依賴「化學自營細菌」來製造生存所需養分。牠們從海底沉積物吸收硫化氫,以及從海水吸收氧氣及二氧化碳,再轉移至鰓細胞內的共生細菌,通過細菌的化能合成作用產生所需的能量及營養物質。有關過程可參考圖1。

研究團隊發現白瓜貝體內與呼吸作用和物質擴散等細胞代謝過程相關的基因家族有所擴張。這些過程包括產生能量和碳合成過程所需的氣體輸送、共生體內的微細分子和蛋白質傳送,以及內共生細菌數量的調控,有利宿主從共生細菌獲取足夠營養。

(二)不再以浮游植物為食物

浮游植物是海洋食物鏈的主要基層食物來源,纖維素酶則是一種能分解浮游植物纖維素的蛋白酶。團隊發現白瓜貝缺少纖維素酶基因,這可能是白瓜貝的祖先為適應由原本以浮游植物作為食物來源,變為依靠細菌供給養份所作出的演化。

(三)硫代謝途徑的適應

這種互惠共生關係的奧秘,亦隱藏於共生細菌的基因組。研究團隊發現白瓜貝鰓內的共生細菌發生了明顯的基因組收縮,僅相等於自由生活的近親物種基因組大小的約百分之四十。然而,其共生細菌的基因組卻保留了完整和活躍的硫代謝途徑,以及合成20種常見氨基酸和其他重要營養素的能力。這些結果顯示出共生細菌所產生的能量和提供的養份,對於維持這種共生關係的重要性。

(四)攜氧能力的提升

血紅蛋白是一種在許多生物的血液和組織中均會發現的金屬蛋白。有別於脊椎動物,軟體動物通常不依靠血紅蛋白來攜帶氧氣。不過,研究團隊卻在白瓜貝體內發現幾種高度表達的血紅蛋白基因,意味著白瓜貝有更高的攜氧能力,以提升在深海低氧環境中生存的能力。

邱教授說:「過去有關深海共生關係的研究,大多數僅集中在細菌上。這是首次同時對棲息於深海的蜆及其共生細菌的基因組進行系統研究。該研究旨在探索共生關係的多樣性以及深海共生體系的進化機制,從而了解無脊椎生物在深海極端環境生存的遺傳機制。」

這項研究由浸大和浸大深圳研究院的科學家,聯同香港科技大學南方海洋科學與工程廣東實驗室(廣州)香港分部、香港城市大學、日本國立研究開發法人海洋研究開發機構、中國科學院深海科學與工程研究所,以及廣州海洋地質調查局共同進行。

邱建文教授(右)和他的浸大研究團隊成員葉志豪博士(中)和徐婷博士,從南中國海一處1,360米深的冷泉區採集到的白瓜貝樣本。

圖1:圖中展示白瓜貝將足伸入沉積物以獲取硫化氫。由於血液中含有血紅蛋白用作輸送氣體,白瓜貝的足與外套膜均呈紅色,這是一種應對低氧環境的適應方式。(浸大學生胡俊彤繪)